Andrew Witkin and I have known each other since we were twelve years old. I wrote this essay for a catalogue of his work on the happy occasion of two 2008-2009 Boston exhibitions, at the ICA and at LaMontagne Gallery.

*****

“Look What Thoughts Will Do”:

Reflections on Some Rooms Our Friend Andrew Currently Occupies in Boston

DOOR

It is not the food bought, but the food processed and made into a meal—it is not the shirt bought off the rack that is you, but the shirt as a component in a composition of attire that informs on you. Whole meals, sets of clothing in action (the soft architecture of the environments that go near us), and collections of commodities assembled into domestic settings—these are the key creations of the material culture of industrial civilization. They are our mirrors; we see ourselves in them. They are our lenses; others read us through them.

– Henry Glassie, Material Culture (1999)

Forget, if you will, if only for the span of these pages, the entire tired discourse of “the artist” and “the curator” and “the gallery.” That persistent modern terminology, with all its vaunted (now limping) romantic aspirations and its implicit (now ingrown) class hierarchy, which valorizes some kinds of human labor over other kinds, is a broken animal. Kick out its broken paws, and let it lie! Work is work, and good work is good work, and good works are good works, creative and valid and artful and useful, whether political or culinary or scientific or automotive or cinematic or whatever. If you live in the United States of America, where many folks are becoming increasingly paranoid of what pundits curse as elitism or exclusivity and what others recognize as the essential culture-hex of advanced finance capitalism, I doubt I am the first to ask this kind favor of you. And in fact, if you’ve been looking and listening, Andrew has asked you already––tacitly, politely, patiently––through the images and objects and groupings he has shared. That is his good work, and these are his good works. Look around some. Call things by their names.

Call him a collector.

Instead of the tortured, misunderstood artist, consider the contented, understanding collector. In our contemporary cultural mythos, the former supposedly angles for notice (if not fame), for public recognition and some measure of specialization, exceptionalism, and immortality, whether economic or canonical-historical. On the other hand (so the legend goes), the collector happily putters away in privacy, foraging, amassing, arranging, middle-manning it. That is of course a gross oversimplification of a potentially specious dichotomy—Duchamp and Cornell and many others busted that door wide open many decades ago––but bear with me. Things are different beyond the clean, well-lit white cubes of the art world, folks; let’s talk about the accumulative acts of not-art collectors, or gatherers, as opposed to hunters.

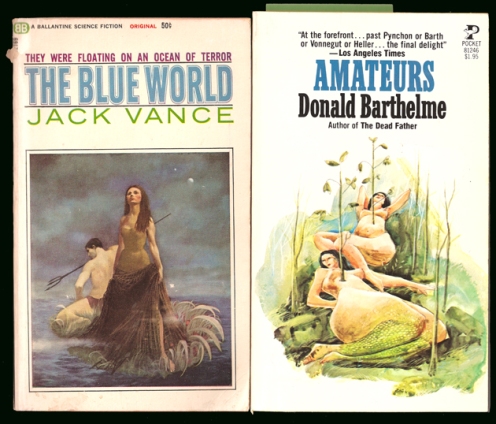

If dichotomies are too messy for you, let’s talk democracy. I’m a collector, as I’m sure you are too. We are all collectors. I collect various things: books, photographs, pickled foods in jars, hats, firewood, records mostly. My collections, like most of those kept and ordered by my generation and subsequent ones, comprise both tangible things and their shadows, information things. And I don’t mean just the synaptic memories and mental feelings that we all accumulate whether we want to or not. Today we can stockpile, compile, and catalog ad infinitum, because the things we collect are not exclusively physical items with an actual dimensional scale, but also digital files of simulacra, binary data that we can cram into and catapult between steadily shrinking plastic consumer containers: mp3s, jpegs, avis, and other mediated acronyms, even digital avatars of human beings in the form of our “friends” on Facebook and MySpace. Hard drives are not so hard to fill up with bullshit, cheaply scored or pirated.

Access is effectively immediate, and the archive is among us, on our bodies and in the ether, in the thickly wired and wireless interstices between our homes. Collecting today, while arguably more ubiquitous and banal than ever before, is also easier than ever before. Our digital collections—I’m thinking of music in particular—are particularly rampant, containing more data than we can experience in a lifetime. The act of collecting involves much less temporal investment and less spatial ranging than ever before, and as such, the pendulum is bound to swing back to other modes that can incorporate a more corporeal devotion. But you don’t need me to explain any of this stuff––prognostications aside, surely you’re hip to all this already. You’ve opened this book, which is a good sign.

*

HALL

Standing on the corner

I heard my bulldog bark.

He was barking at the two men

Who were gambling in the dark.

Stagger Lee and Billy,

Just two men who gambled late.

Stagger Lee, he threw a seven.

Billy swore he saw an eight.

Stagger Lee went home,

They say he got that big old forty-four.

Said, “I’m going to that barroom

“I’m gonna pay that debt I owe.”

“Stagger Lee,” cried Billy,

“Oh please don’t take my life,

Cause I got so many children

And a very sickly wife.”

Stagger Lee, he shot poor Billy.

Oh he shot that boy so bad

When those bullets went through Billy

They broke the bartender’s glass.

Should I take it––

Should I take it real slow

Oh Oh Oh

Oh Oh Oh

Oh Stagger Lee

Oh Stagger Lee

– “Stagger Lee,” American traditional (arr. Terry Melcher, 1974)

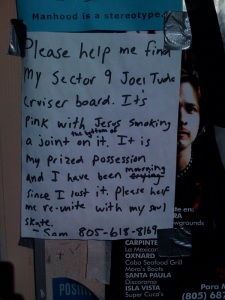

One thing our friend Andrew does really well is lists. Lists are their own kinds of collections, catalogs of words, which are themselves representations of other collections. Text, both appropriated and authored, appears throughout his archives and artifacts, often in staccato list form, and yet, for as long as I’ve been knowing him—sixty percent of our lives now—he has insisted that he is not “a writer.” OK, so he’s neither “artist” nor “writer,” but let’s stick with “collector.” Of friends’ birthdays, for instance. Of all kinds of books, music, photographs, and artworks, yes, but also of word data, list data, and anecdotal minutiae, some of it quite personal and some of it bluntly public domain. What lies between the lines?

One of his collections is an iTunes playlist of every recording he has been able to find of the archetypal African American badman song and toast “Stagger Lee.” The song is a vernacular transposition probably based on real-life Lee Shelton, a pimp who killed William Lyons on Christmas Eve, 1895, in Bill Curtis’s saloon in St. Louis. Andrew and I share a fascination with this tune, which we’ve both addressed in visual as well as musical terms. Andrew made a sound collage in 2004 called “Stagolee,” which digitally collapsed the entirety of his still growing collection of recordings into a dense, symphonic buzzsaw the length of the longest version of the song. The sustained appeal this blues ballad holds for two thirty-something white men from the Northeast is a subject for another essay, but the legend, in its many articulations, goes roughly like this:

“Cruel cruel” Stagger Lee (aka Stagolee, Stag Lee, Stack O’Lee, Stackalee, Stackerlee, Stack Lee, and other variants) is one bad motherfucker. He and Billy Lyons (aka Lyon or De Lyon) get to gambling late one night, down in a place near the bordello known as the Bucket of Blood. One of them, probably Billy, cheats at cards or dice, and somehow, either through theft or a fraudulent bet, Billy gets a hold of Stag’s brand-new white Stetson hat, which may or may not have magical properties. Enraged, Lee goes home to fetch his gun, and returns to shoot Billy, who pleads for his life on account of his family. Sometimes additional barroom mayhem and violence ensue; sometimes sexual jealousy is a motive; Billy almost always dies. Occasionally, Stag’s woman Stack O’ Dollars shows up. Stag often ends up on trial or in jail, where he insults the court, or even in hell, where he has been known to sodomize the devil. He’s that bad.

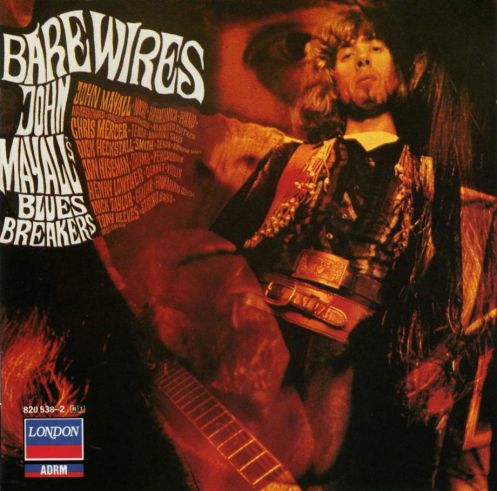

The song has slithered through blues, r&b, string band, country, and rock idioms for over a century, always disreputable and always mean, but often difficult to recognize harmonically or melodically. It’s hard to beat Mississippi John Hurt’s gently menacing country blues version—or its opposite, the uptempo boogiefied Youngbloods version—but out of all the worthy, wildly disparate articulations, I’ve always had a special affection for Terry Melcher’s, just for its sheer spitshine artifice and strangely incompatible timbre. His rendering builds from a disconcertingly mellow, chiming guitar introduction to a burnt-moustache beach-weirdo midsection into an abrupt choral fade-out featuring his mom Doris Day’s backing vocals. The narrative and pacing feel truncated and rushed, and the whole tenor of the affair is just slightly off, overproduced and caked in a California cocaine glaze, but it’s somehow irresistible and powerfully affecting anyway. A year or so ago I finally sent Andrew the mp3 to add to his ongoing iTunes playlist. It sits in a good spot, actually—between Taj Mahal (whose band the Rising Sons Melcher was instrumental in signing to a record deal) and Tim Hardin.

Before submitting to his collaborative, omnivorous list, I did not tell Andrew anything about Terry Melcher and his charmed/damaged, spooked/gilt life and its bloody resonances with the Stagger Lee myth. So here’s my own Melcher obit-list, Andrew, an anecdotal dissection of the data already swallowed up by your hungry practice:

• He was born in 1942 to Doris Day and her then husband, trombonist Al Jorden.

• He formed the bands Bruce & Terry and the Rip Chords with future Beach Boy Bruce Johnston, beginning a lifelong interest in hot rod and surf music songwriting and production techniques.

• He produced early Columbia records by the Byrds, Paul Revere & the Raiders, and the Mamas & the Papas, among many others.

• He introduced Brian Wilson to Van Dyke Parks and sang backing vocals on the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds.

• He befriended Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys; together with Gregg Jakobson, they established a blonde gang known as The Golden Penetrators, whose sole charter was to drive around L.A. in their extravagant cars looking to pick up girls for casual sex (Beach Boys groupies were a sure bet).

• “We’re high-rollin’ studs from L.A.” (“High Rollers,” 1978)

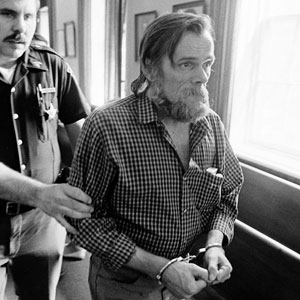

• He was introduced to Charles Manson by Dennis Wilson in 1968. After initial interest in recording Manson’s music, Melcher turned him down after a botched audition and evidence of his erratic violence.

• He rented his house on Cielo Drive in L.A., which he formerly shared with girlfriend Candace Bergen, to Roman Polanski. On August 9, 1969, Charlie Manson’s “family” brutally murdered Abigail Folger, Voytek Frykowski, Jay Sebring, Steven Parent, and Polanski’s pregnant wife Sharon Tate in the same house.

• “Family” member Susan Atkins claimed in testimony that they intended to target Melcher because of his perceived slight to Manson, though it was soon revealed that Manson knew that Melcher no longer lived in the house.

• Terrified, Melcher hired a bodyguard and underwent psychotherapy.

• He recorded two tepidly received, decadently produced solo records, the slyly ironic L.A.-scape Terry Melcher (1974)—with an all-star band featuring Ry Cooder, Doris Day, Chris Hillman, Sneaky Pete Kleinow, Spooner Oldham, and Clarence White—and the Old Mexico and gambling themed daiquiri-fever-dream Royal Flush (1978).

• He produced the notoriously overdubbed 1971 Byrds record Byrdmaniax, which has been referred to as “Melcher’s Folly.”

• He produced The Doris Day Show.

• He co-wrote the 1988 Beach Boys comeback smash “Kokomo” with Papa John Phillips of the Mamas & the Papas, Scott “If You’re Going to San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)” McKenzie, and Beach Boy Mike Love, earning himself a Grammy.

• He produced Summer in Paradise (1992), the final Beach Boys studio record and the first album ever recorded with Pro Tools.

• He died in 2004 at age 62, after a long battle with melanoma.

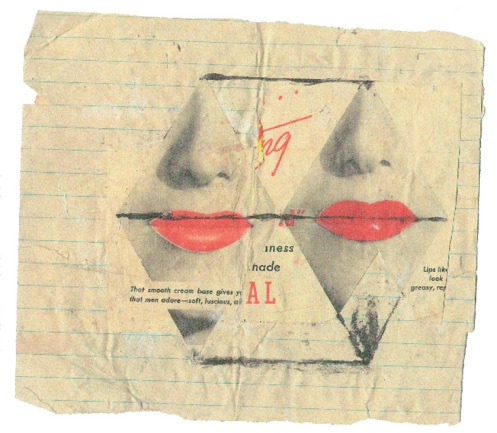

The archive has already absorbed all of this data. Nested within the Stagger Lee archive is another story of a very different sort of homicidal maniac, Charles Manson. This history, as esoteric and minor as it may appear to the casual viewer of Andrew’s work, resides inside his oeuvre. Andrew’s data, like all collections, is recursive; each unit, each manufactured artifact, contains other anecdotes and narratives, in an endless helix. The fossil record is deep. We are not privy to much of this information—in many cases, images or documents are stacked or bundled to efface or hide their legibility—but the data is there nonetheless, honey in the rock.

Andrew has abiding interests, and he nurtures those interests daily, suturing them to domestic reflections and to the awed archeology of wandering, wondering knowledge. Here the archive (after Foucault, but who cares?) becomes an active organ of discursive meaning-mapping, fodder for a feast of engaged show-and-tell exercises. Above all, our friend Andrew offers dialogue. That is his work––that is what his work yields for mute objects and lonesome letters and faraway friends. He allows no one atomic element to stand on its own as given, but leaves the manifold component conversations to insulated chance. Here Terry and Billy cross paths with Charlie and Stack. Who lives in your collections, the things that sit on your bureau and bedside table? Bring ‘em out! No one should ever be alone or without their own and borrowed memories, and minimalism is a sad fart in a world that produces Stagger Lees and Charlie Mansons.

*

ROOM

On the third night following the arrival of the party in the city, Pierre sat at twilight by a lofty window in the rear building of the Apostles’. The chamber was meager even to meanness. No carpet on the floor, no picture on the wall; nothing but a low, long, and very curious-looking single bedstead, that might possibly serve for an indigent bachelor’s pallet, a large, blue, chintz-covered chest, a rickety, rheumatic, and most ancient mahogany chair, and a wide board of the toughest live-oak, about six feet long, laid upon two upright empty flour-barrels, and loaded with a large bottle of ink, an unfastened bundle of quills, a pen-knife, a folder, and a still unbound ream of foolscap paper, significantly stamped, “Ruled; Blue.”

– Herman Melville, Pierre, or the Ambiguities (1852)

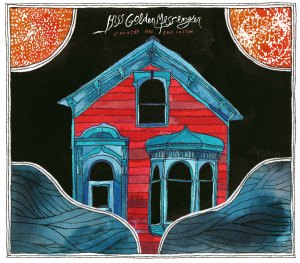

Here’s some history. If horror vacui—a fear of emptiness—characterized the cluttered aesthetic sensibility of the collectors of Victorian industrialism, then the contemporary conjuncture of data-glut and rapidly devoured open spaces suggests the advent of a kind of nostalgia vacui. (By the way, collage is a vernacular tactic, not some magical modernist invention!) This potential nostalgia for spatially arrayed information––for fresh, composed space, for the unabashedly sentimental echo of bare tables and bare beds––is what Andrew proposes with his work. It’s no coincidence that Yves Klein’s notion of “Le Vide” is a perennial touchstone for him, even appearing as an explicit allusion in his own work. But aesthetics in Andrew’s work sound in counterpoint to information compulsively ordered and re-ordered.

Andrew offers an intermediary data system that overlays the deliberate taxonomy of the archive onto the satisfyingly palpable presence of objects found, appropriated, and customized. But the central display objects of his installations feature a bland, generic execution that gestures towards the emptiness of these everywhere data-things and their opposition to objecthood. Metaphorically he reconciles data-things and thing-things, the architectural rigor of the perfect library with the hollow falsity of our more ersatz collections. The simple plywood shelves, tables, beds, boards, dressers, et al. that Andrew constructs are all spartan symbols of more substantial and well-worn home ideals; they are half-things, ghost-things, mock-ups that draw our attention to the collections on and in them or not on and not in them. These furniture framing devices are unique, and built to spec, but they are decidedly contingent, makeshift. They offer neat, blank surfaces and spaces for lived-in and lived-with jackets, socks, shirts, blankets, towels, boxes, photographs, bottles, tools, bones, and other ephemera. Their provisional, prosaic construction is diagrammatic and unsteady at best, spindly and rickety at worst, and plainly unable to support human weight, despite the tidy and often elegant construction. They cannot function as functional furniture, and yet they are the components of his inhabitations that perform the crucial task of scaling the evidence to the human body, toward the humanity and mortality of the artifacts and the whole tradition of gathering and archiving mementoes.

Vanitas!

These stark forms, these wooden keels, have another efficacy as well. They behave as framing indicators––humble stand-ins, surrogates, and synecdoches for presentational and behind-the-desk museological facts like pedestals, vitrines, specimen cases, shelves, desks, work tables, and flat storage. Andrew lives intimately with these kinds of forms—remember that his day job, an intrinsic part of his making, is dealing and curating contemporary art at a prominent Boston gallery. He literally looks at and arranges things for a living, abetting the habits of other collectors. To a great extent, his practice responds to his experience as a gallerist and an archivist––documenting, collecting, arranging for visual and intellectual pleasure––but it is simultaneously antithetical to normative notions of art-world market viability.

(At the moment, those bottom lines have been lamed by what the radio heads call the “global economic crisis,” the result of randy trading in imaginary fiscal products with preposterously abstract names like “futures” and “securities.” Aren’t you glad for Andrew’s old towels, so like your own?)

Is it finally time then for the obligatory art-historical fingering? His installations read as fundamentally unassuming sketches of functionality, neither as fussily and self-consciously museological as Mark Dion’s displays, nor as theatrical, untamed, and scavenged as Dieter Roth’s archives. And why should they be? Andrew plumbs another sort of home order, playing with systems that chart the phenomenology of domestic everydayness and its interlocking rhythms—that’s philosopher Henri LeFebvre’s notion—rather than flaunting knowledge or exhibitionism or chaos. No flagrante delicto moments here, just stringent plainness, or “normalism,” as Andrew himself once deemed his own methodology. The most radical thing about the work is this: it’s somehow essentially banal, quotidian, buttoned-down, boring, ordinary… and therein resides its true-gotten beauty. What is real, what is really there, what is important, what is the distinguishable difference between these objects and arrangements as they appear here—say at the ICA—or in Andrew’s bedroom? These are the ripest of Ambiguities.

My friend Will—he’s Andrew’s friend too—recently drew my attention to a remarkable 1965 sculpture by Michelangelo Pistoletto, one of his so-called “Minus Objects.” Entitled “Lunch Painting,” it’s a minimalist plywood frame-box that sits against the wall, with a table and two chairs built into its radically simple geometry of eleven plain plywood planks. Here we have a certain kinship of Ambiguities and Invitations-to-Stay-Awhile. Come in, these two makers say, here is something familiar.

Andrew’s rooms, immaculate, antiseptic voids when the well-meaning gallery or museum presents them, rely on their adopted frame architecture, indicating a thorough contextualism, a desire to showcase and to share and to sit-in. That is not the case in his own home, or the homes of others in which he has shown; those spaces already enjoy a human-scaled sense of space. They already have the decidedly comfier furniture that his plywood objects reference, so much the better to serve as ready, site-specific surfaces for his collections. And until recently, Andrew’s collecting practice remained largely inside his own home, available to all friends and visitors but inherently private nonetheless. These important sharings in public venues represent an extension of a home life that is deliberately aestheticized, but wholly welcoming.

Andrew inhabits spaces, rather than exhibiting in them, and that I believe is a crucial distinction between an artist and a collector, or between an artist and a human being.

DOOR

“GOAT COAT! GOAT COAT!”

– Andrew Witkin, from the 1996 poem “Against Fabrication”

Chapel Hill

December 22, 2008

Posted in arts, boogie, words